African Center for Consultancy

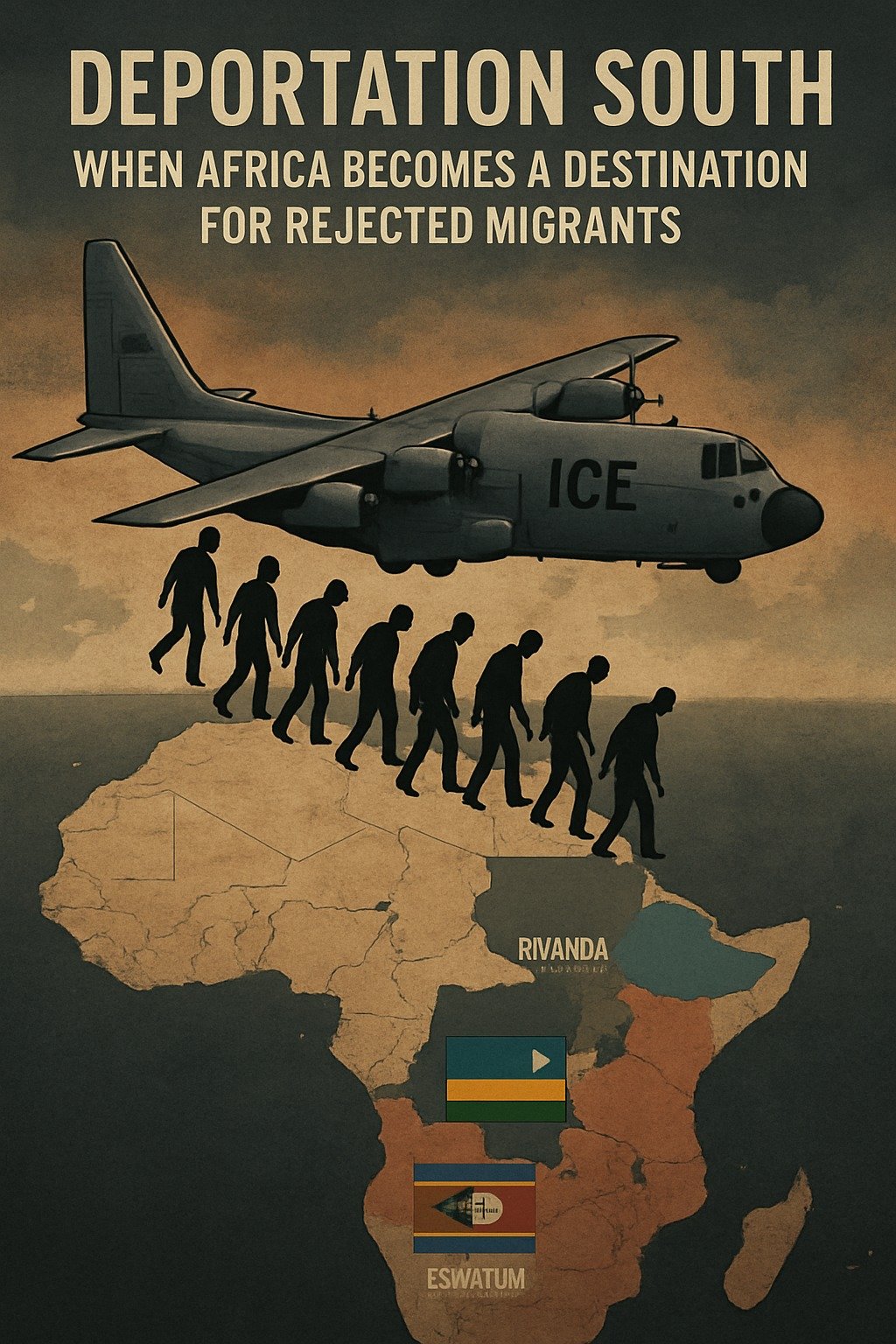

The return of Donald Trump to the White House in January 2025 marked a pivotal shift in migration policy—not only within the United States but globally, and particularly in Africa. From the early days of his second administration, Trump began reactivating his hardline policies toward migrants, based on an extreme security approach that views the expulsion of "non-Americans" as a pillar of restoring what he calls "state prestige" and protecting "national identity."

In this context, deportation policies are no longer merely a matter of domestic law, but have transformed into diplomatic tools used to strike deals with countries in the Global South—especially in Africa—to externalize the migration crisis. This strategic shift reflects an expanded vision of the "America First" doctrine, now infused with new security and racial overtones.

As reported by The Washington Post on April 30, 2025, the U.S. administration reached an undisclosed agreement with the government of Rwanda to accept a number of undocumented migrants detained on U.S. soil in exchange for financial incentives and direct developmental aid to Rwanda’s health and education sectors. Rwanda officially confirmed in a statement on August 4, 2025, its acceptance of up to 250 deported individuals from the U.S. under what was described as a “joint humanitarian cooperation agreement” (as reported by Reuters, August 4, 2025).

Simultaneously, the Associated Press revealed that the U.S. had already begun deporting migrants to other African nations, notably the Kingdom of Eswatini, which received a number of deportees in early July 2025 under secret arrangements not publicly disclosed (as noted in an AP report dated August 2, 2025). Leaked information indicates that Eswatini received promises of financial support and infrastructure projects in exchange for cooperation.

These developments followed a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court on June 23, 2025, which removed legal restrictions on deporting individuals to “third countries,” including those with no asylum or protection agreements with the U.S. This ruling legally paved the way for these controversial arrangements (U.S. Supreme Court Ruling No. 23-113).

According to assessments by the NYU Center for Legal Studies, the ruling “opens the door to the creation of a global system of human deportation, turning developing countries into human warehouses for America’s crises” (NYU Legal Studies Center Report, July 2025).

Implications for Africa: The Continent as a Site of Demographic Engineering

The use of African countries—especially Rwanda and Eswatini—as reception zones for migrants with no prior connection to these nations represents a dangerous transformation in North-South relations. Africa, once again, becomes a geographical space for the implementation of global policies that disregard human dignity and national sovereignty.

In Rwanda’s case, the state is investing in reproducing an image of itself as “safe and stable” to attract investments and political deals, much like it did with the United Kingdom in a similar 2022 agreement. In Eswatini’s case, the motive appears purely economic amid declining development indicators and chronically deteriorating infrastructure.

However, these policies come with medium-term risks—both security and social. They are likely to provoke local tensions, especially in resource-scarce settings and in the absence of legal protection frameworks for deportees.

Human rights organizations like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have warned that such policies “legitimize the export of suffering rather than addressing it” (joint statement, August 5, 2025).

Historical Roots of Deportation from America to Africa

The use of Africa as a deportation destination by the U.S. has colonial roots that intersect with America’s own racial history. In the early 19th century, the American Colonization Society (ACS) was founded to resettle freed Black Americans in Africa, leading to the establishment of Liberia in 1822. This coerced “return,” masked as a liberation project, was in fact a means to remove Black populations from the white colonial American order.

According to the Library of Congress archives, this resettlement project was supported by powerful white American elites and funded by successive administrations through the 19th century (Library of Congress, Global Migration Series, 2020).

In the 20th century, the U.S. continued to use mass deportation—though not toward Africa—to manage internal crises. Notable examples include:

- The Great Depression (1930s): At least 400,000 individuals of Mexican descent were deported in so-called “voluntary return” campaigns aimed at ethnic and economic cleansing (Politico Report, December 2024).

- Operation Wetback (1954): Over one million Mexican migrants—including U.S. citizens—were deported in the largest mass deportation in modern U.S. history (Department of Homeland Security archival report, 2019).

This long history shows that deportation has been less about legality and more about crafting a racially homogenous national identity—revived during periods of internal crisis.

Legal Foundations and Modern U.S. Migration Policies

Over recent decades, U.S. migration law has shifted toward greater severity, particularly post-9/11, which redefined both national security and immigration as intertwined issues.

Key legislative milestones include:

- IIRIRA (1996): The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act introduced "expedited removal," allowing deportation without court hearings for individuals unable to prove two years of continuous U.S. residence or who provided false entry information (Congressional Immigration Report, 1996).

- Title 42 (2020): Under Trump, a health-related statute was invoked to expel migrants under the guise of COVID-19 prevention, denying them the right to seek asylum. Hundreds of thousands were deported until the rule was lifted in 2023 (CDC and CBP Reports, 2020–2023).

- Third-Country Agreements (2025): Trump’s second term saw the revival of deals with poor and politically weak countries to receive undocumented migrants with no ties to them—like the Rwanda model—effectively redefining “deportation” as cross-border demographic engineering.

These shifts received crucial legal backing in the June 23, 2025, Supreme Court ruling permitting deportation to countries lacking protection or asylum treaties with the U.S. (Ruling No. 23-113).

Timeline: Deportation Agreements to Africa in 2025

2025 represents a turning point in globalizing the U.S. migration crisis and shifting it onto African soil. Key milestones include:

- January 2025: Trump sworn in and declares immigration a top national security priority.

- March–April 2025: Leaked reports suggest secret U.S.–Rwanda negotiations to transfer undocumented migrants. The Washington Post confirms financial and health/education aid in return for migrant intake (April 30).

- May 2025: First deportations to South Sudan. Some deportees reportedly mistreated on arrival (AP, May 2025).

- June 23, 2025: Supreme Court clears legal path for deportations to “unsafe countries” (Ruling 23-113).

- August 4, 2025: Rwanda officially accepts 250 deportees. Reports confirm simultaneous transfers to Eswatini (Reuters and AP, August 4).

This sequence illustrates not just implementation phases but a rapid acceleration in externalizing the migration crisis to Africa under opaque political frameworks.

Political and Economic Dimensions

Political-Security Objectives:

Trump’s administration uses migration both as campaign material and a foreign policy tool to pressure developing nations. The “Rwanda model” shows how an African state can be integrated into a broader American strategy to deflect domestic crises through externalization.

Economic Incentives:

These agreements exemplify a new form of “geopolitical bartering” where migration is used to extract asymmetric economic benefits. The U.S. aims to cut the rising costs of internal migration management, which ranges between $150–$300 per migrant per day in ICE facilities (DHS Inspector General Report, 2023).

In return, African nations receive:

- Direct funding for reception centers.

- Infrastructure and development aid.

- Promises of future partnerships in tech or energy.

For instance, Rwanda’s acceptance of 250 migrants in June 2025 came with a $75 million U.S. aid package over three years to build “humanitarian reception centers” and “community integration programs” (Rwandan Ministry of Interior, June 24, 2025).

Yet, such “deals” raise deep ethical questions. They commodify migrants in unequal exchanges that use human suffering as bargaining chips without genuine concern for their rights or participation in shaping their futures.

Moreover, this dynamic creates a parallel economy of forced migration, incentivizing some African regimes to pursue further agreements for short-term financial relief, while ignoring long-term social and legal ramifications.

In essence, the economic aspect cannot be separated from the ethical. It introduces a disturbing logic into international relations: “land for people,” “aid for silence”—a reality that demands principled resistance from African civil societies and political elites.

Legal and Humanitarian Concerns: A Threat to International Norms

Deporting undocumented migrants from the U.S. to African countries with no legal, ethnic, or geographic ties to them poses a fundamental challenge to international law and human rights standards.

First, legally, such transfers violate the principle of non-refoulement under the 1951 Refugee Convention, which prohibits returning individuals to places where they may face danger or inhumane conditions.

Amnesty International warns these policies “turn poor countries into temporary human warehouses for money, without regard for the migrants’ psychological, legal, or social well-being” (Amnesty Statement, August 5, 2025).

Second, many of these bilateral agreements reportedly bypass local legislative processes or public debate. In Rwanda, for instance, the deal was signed via presidential decree without civil society consultation—raising questions about domestic legal legitimacy.

Third, from a humanitarian perspective, deportees—often vulnerable people like asylum seekers or stateless individuals—are suddenly placed in unfamiliar environments with no legal or social support. Cases from the UK–Rwanda deal in 2022 showed deportees refusing to leave shelters, some attempting suicide or escape due to despair.

Most host countries lack functional asylum systems or legal infrastructure for complex issues like legal status or family reunification. A June 2025 UNHCR report noted that “reception centers in countries like Eswatini and Rwanda are ill-equipped for long-term protection, operating more like transit hubs with no clear resettlement plans.”

Symbolically, these policies evoke colonial practices—using African lands as dumping grounds for foreign crises, with little regard for African dignity or sovereignty.

Ultimately, forced deportation to unrelated third countries sets a dangerous legal precedent that could be abused by other nations to shirk humanitarian obligations—undermining the global refugee protection system and eroding justice rooted in human dignity.

Urgent political pressure is needed—from international and African actors alike—to halt such practices, enforce transparency, and ensure respect for international law, especially when the world’s most vulnerable are at stake.

Geopolitical Dimensions: Asymmetrical Deals and Global Power Play

At the heart of these policies lies a broader geopolitical reconfiguration of North-South relations. Deporting migrants with no African ties to African states in exchange for financial incentives amounts to a form of unbalanced contracting—power exercised by the Global North in return for sovereignty concessions by the Global South.

According to the Center for International Policy (Washington, 2025), these deals “entrench a new form of dependency, where African countries are coerced into roles that serve Western crisis management strategies rather than their people’s interests.”

Such deportations cannot be divorced from post-COVID global restructuring, the Ukraine war, and economic crises. With far-right forces rising in the West, migration is weaponized for domestic consolidation while outsourced abroad.

Africa becomes the preferred experimental field for these policies, given many countries’ economic fragility and political vulnerability. Targeting Rwanda, Eswatini, or even Chad (in future) reflects this broader trend.

These strategies also reinforce colonial perceptions of Africa as an “empty space” suitable for receiving the “excess humans” of the Global North—reviving the logic of colonial deportations.

Moreover, deals are often struck with unrepresentative political elites in exchange for ongoing foreign support, bypassing democratic processes and weakening Africa’s collective bargaining power.

Geostrategically, such developments may open the door for other powers—China or Russia—to exploit this Western ethical vacuum and expand their influence by offering alternative migration and development approaches, potentially reshaping African alignments in the future.

Thus, these deportation schemes are not merely migration policies. They are instruments of global power projection—disguised as aid, investment, or partnership, but rooted in coercion and the commodification of vulnerable lives.

Conclusion

The deportation of undocumented migrants from the United States to African countries like Rwanda and Eswatini represents a highly sensitive development in global migration governance. While officially framed as a national security necessity, these policies reveal deeper shifts in the nature of North–South cooperation and the framing of “alternative solutions” to migration dilemmas—solutions based on expulsion, not root-cause remedy.

The willingness of some African states to accept deportees—whether for political leverage or economic gain—raises profound questions about national sovereignty and ethical negotiation limits, especially when the targeted groups are poor, stateless, or fleeing war-torn countries.

Hence, there is an urgent need for oversight, advocacy, and accountability to ensure that these agreements uphold migrants` fundamental rights and prevent Africa from being used as a staging ground for solving others’ crises.

A just future for migration will not be built through deportation and outsourcing—but through solidarity, development, and the protection of human dignity.